REVIEW: The Life of Chuck is an Unabashed Tribute to 90s Feel-Good Schmaltz

Mike Flanagan's take on the Stephen King tale has moments of beauty but buckles under the K-Pax/August Rush/Pay It Forward of it all

There was a very specific type of movie that was made from about 1995 to 2010. Call the genre “Wowie wow! Ain’t life somethin’?” These movies were defined by their aggressively uplifting tone, saccharine sincerity, Oscar-bait-y performances, and more often than not a misunderstood male child (usually brunette, usually with glasses) whose wide-eyed wonder could Teach Us A Thing Or Two About Life. The trend was kicked off in earnest with Forrest Gump and had what I assumed was its last hurrah with 2011’s Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close. Other notable entries include K-Pax, August Rush, Simon Birch, I Am Sam, Finding Neverland, and my personal least favorite, Pay It Forward.

It comes as a mild surprise, then, that last year’s winner of the prestigious Toronto Film Festival Audience Award went to an unabashed throwback to this goopy, sugary genre: Mike Flanagan’s The Life of Chuck.

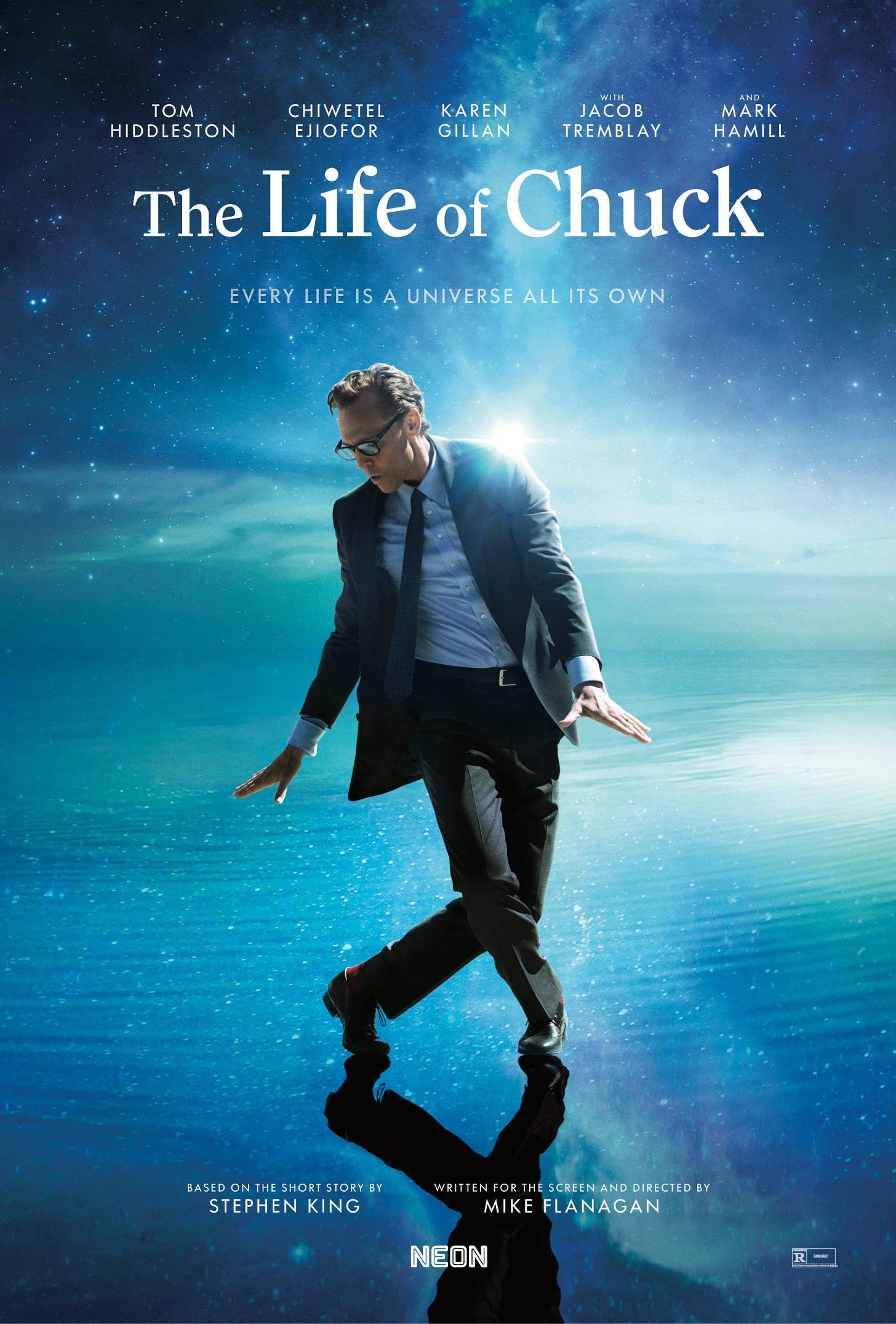

Just look at the poster. If it doesn’t scream heartwarming 1998 film starring Kevin Spacey that makes $47 million, has at least two songs from The Temptations on the soundtrack, and gets one and a half stars from Roger Ebert, I don’t know what does:

Now, that’s not to say this film is anywhere as unbearable as some of its cinematic ancestors. It’s not. But its playing in a schlocky genre that is very challenging to get right without being eye-rolling.

On the plus side, it is helmed by Netflix horror maestro Mike Flanagan (creator of the excellent Midnight Mass, Fall of the House of Usher, and The Haunting of Bly Manor series, among others). On the downside, Flanagan has to adapt a rather antiquated Stephen King short story that, at times, feels at times as syrupy as a Candyland board.

As I watched the film unabashedly unfold in front of me, I kept thinking…someone made this type of movie? In this economy? Maybe it played better last fall in Toronto, before phash-ism took over, when there was still an iota of hope things could get better? You know, before *gestures broadly at literally everything happening every single day*?

Like, the idea that a film like this could still exist in 2025 isn’t a bad thing. We all need a little uplift. But does it work?

Let’s break it down.

A Sugar Rush in Three Parts (Like A Fun Dip? Remember Fun Dips?)

The film is divided into three sections, presented ostensibly out of chronological order, but all dealing in some way or another with the life of Charles Krantz, an accountant.

Flanagan’s script relies heavily on narration from Nick Offerman to table set during these sections, explain inner emotions, and sew everything together. Offerman has a perfect voice for narration, but the near-constant use of his voice offers clarity just as often as it highlights the film’s biggest weaknesses, which is that it can’t fully escape its stilted writerly tendencies and be authentically alive.

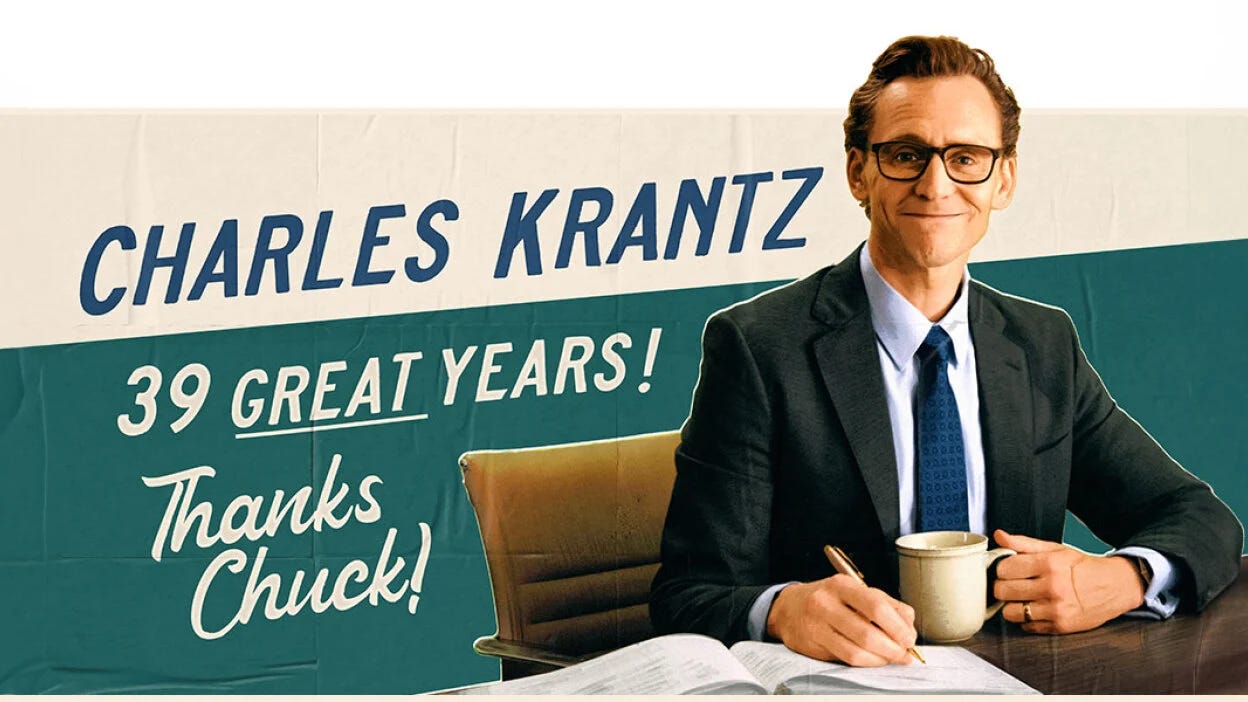

The first section is intriguing and unsettling. Chiwetel Eijifor is Marty, a checked-out high school teacher living, we learn, in very strange times. Natural disasters are abundant, people are losing their will to keep society going, and there’s a zombie quality to life, with people shuffling through their days as everything crumbles around them. His ex, Felicia (Karen Gillan), is one of the few remaining, very exapserated nurses at her hospital. Seperately, both start seeing strange billboards around town, and ads on TV, thanking a mysterious man named Charles Krantz (Tom Hiddleston) for “39 great years.” This section is the most visually interesting of the film, and Flanagan does his best to present what feels like a fresh and somewhat prescient take on what the near-future could be like. It also contains two of the film’s best, quick performances: my himbo king Matthew Lillard as Marty’s barely-holding-it-together neighbor and the legendary Carl Lumbly as a Sam, an older, reflective gentleman Marty meets while walking.

The second section is pure wham-o, blam-o schmaltz. We’re at an outdoor shopping center. A woman sits at a drum set. There’s a tediously long, quaint description of how a busker thinks, how she finds her beat that, instead of injecting the vocation with energy and magic, makes it feel knobby and stiff.

She finds the beat. A man in a suit (you guessed it, Tom Hiddleston again) steps from the crowd and decides to dance. He pulls a redheaded stranger from the crowd and they begin dancing up a storm, in way that would make Lee Ann Womack so very proud.

Suddenly, we’re in the world music scene of Mr. Bean’s Holiday. Wow! Life is about going for it! Living out loud! The dream of 90s feel-good cinema is alive in this shopping square!

Yes, there is more going on than just the dancing. Offerman’s thorough narration tells us as much. Hiddleston is very game for the role, throwing himself into the dance sequence, yet there’s an bland everyman nature to his character that makes subsequent revelations feel muted. Part of this is by design, as his character is meant to be a dull accountant suit, yet there’s an anonymity to adult Chuck that feels like a missed opportunity.

The last section is the most interesting and is somewhere between the first and second in terms of saccharine levels. It follows a young Chuck (Benjamin Pajak) and teenage Chuck (Jacob Tremblay) as Chuck grows up with his grandparents. His grandmother (Mia Sara) is loving and warm and likes to dance in the kitchen. His accountant grandfather (Mark Hamill) is bit more gruff, likes to drink, and is weirdly protective of a locked cupola at the top of their big Victorian house. Chuck is never to go in there, ever.

Young Chuck is awkward, curious, and finds his groove through a dance club at school (led confidently by Flanagan stalwart Samantha Sloyan).

There are parts of this section that are genuinely fascinating as Chuck navigates his complicated grandfather, finds his passion and confidence, and searches for answers to the mysteries surrounding him. I will say, the final reveal at the end is beautifully done and pure Flanagan magic.

The third section also contains by the far the strongest scene, which is when a disheartened Chuck talks to his hippy-dippy teacher Miss Richards (the exquisite Kate Siegel) after class and she explains to him the way we create universes between our ears. Flanagan has a penchant for meaty monologues about life and existence and who better than his real-life wife (but let’s be honest, Siegel is so much more than that) to turn one into a grand slam moment.

Therein also lies the frustrating experience that is The Life of Chuck. It does have new and interesting things to say about why we’re here and sometimes it elucidates them with disarming, poetic simplicity. Yet it also, too often, gets bogged down in its own sentimentality and detached descriptions to the point it feels entirely artificial and removed from any truth it might be seeking to impart.

Flanagan regulars like Siegel, Sloyan, and Rahul Kohli (who plays a fellow nurse with Gillan) fare the best, unsurprisingly, as they have keenly developed ears for Flanagan’s dialogue. Hamill, Hiddleston, Gillan, and Ejiofor also do well, but get slightly more caught in the sentimental muck that bleeds through from King’s short story.

Ultimately, Flanagan’s strengths (tone, suspense, deeper meaning in the human condition) feel, more often than not, at odds with King’s goals (lengthy descriptions of busker drummers). But, in the few moments the two voices actually syncopate (like the answer to the cupola mystery) the results are stunning. I just wish the two voices could’ve found the same beat.

GRADE: C+

Thank you for reading Hollywood On The Loos! Please like, share, subscribe, and comment! I make absolutely nothing doing this, so if you like what you read please toss a few coins in the Tip Jar!